One of the many painful things about learning Japanese was learning how to use a Japanese dictionary. It is something that students aren’t usually taught by native Japanese. They already know how to use a Japanese dictionary and input Japanese into a PC or smartphone. It seems not to have occurred to any of my instructors to discuss how to get an alternative character set on your PC or phone and how to look up a word in a dictionary.

Japanese learners owe a huge debt to Jim Breen at Monash University in Australia. Way back in 1991 he started a project that became the EDICT / JMDict Dictionary File. It is a public domain multi language Japanese dictionary database. Prior to this most electronic Japanese to English dictionaries were expensive proprietary devices designed for Japanese speakers to look up English. Almost every dictionary application on the web and the various smartphone dictionaries use Jim Breen’s data file. So the all dictionary programs may have better or worse usability and search logic, but nine out of ten times the definition they provide will be identical. The exception to this is the dictionaries designed for native Japanese speakers to look up English. That’s a topic for another day.

As an Android user the dictionary on my phone that I use all the time is called Aedict. One of the interesting things about whatever he used to develop the application is that he als runs a web version that is identical to the phone application. It’s available here:

So let’s suppose that you are reading some Japanese and come across the following word:

出る

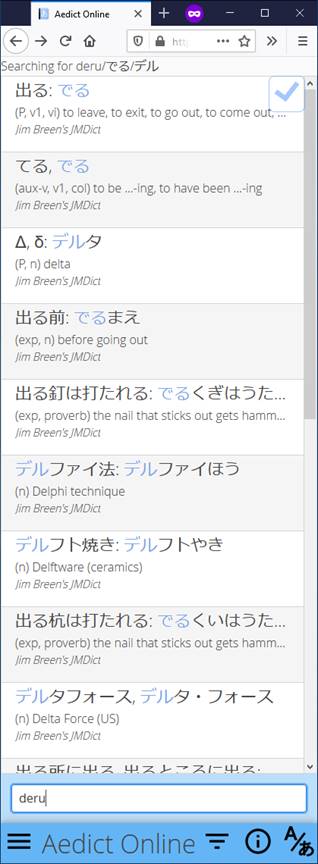

What do you do if you have no idea how it is read or pronounced? If it’s on the computer the easiest thing to do is copy the word and past it into the dictionary. If you can’t do that you got several options each of them increasingly annoying. First, let’s suppose you actually know the reading – in this case it is “deru”. I can type that in romaji right into the search box.

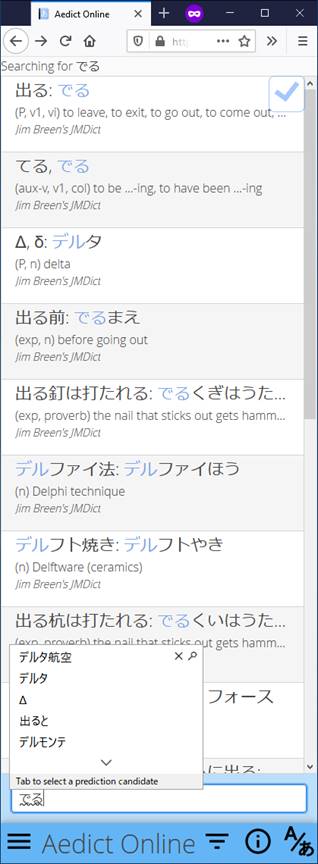

Your second option is to actually type the word in either hiragana or katakana. The dictionary will recognized the hiragana or katakana the same as if you used romaji. However, your phone (or here my Windows 10 PC) will also bring up list of characters that are written with those same hiragana characters. Take a look in the middle of the box in the second illustration.

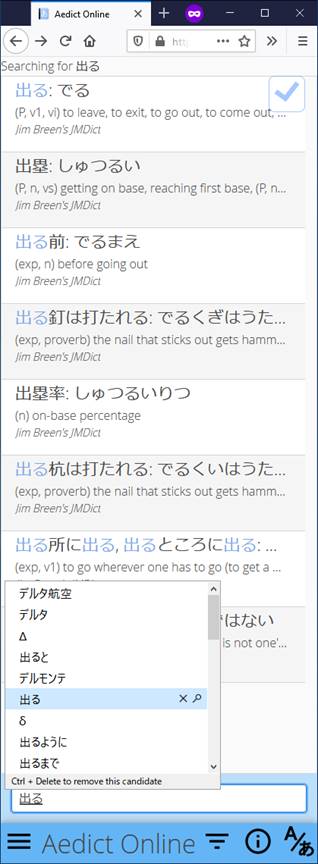

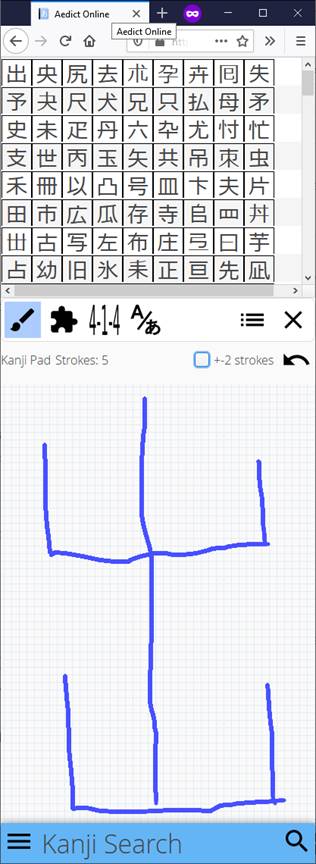

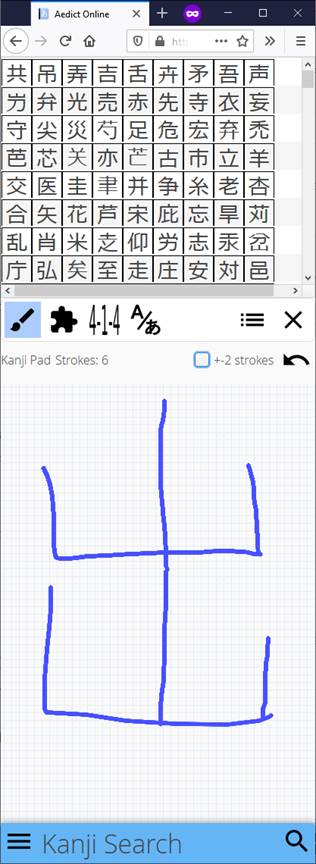

Next, let’s suppose the character is physically written somewhere and you have no idea what it means or how to read it. You have several options. Below you see icons for a paintbrush or fude brush a puzzle piece and 4-1-4.

I’ll skip the puzzle piece and 4-14 approaches as those particular methods work based on the structure and shape of the character and the number of strokes and are even more complex. Instead let’s focus on the paintbrush. We can actually draw the character right on the phone! (Or in the example below with my mouse – which explains why it looks so bad.)

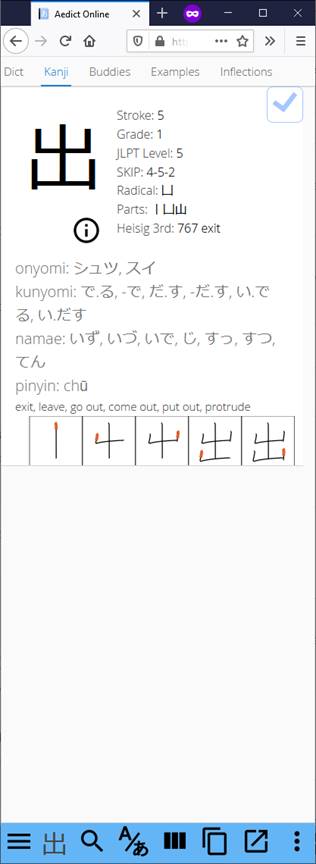

The problem is that all of the character drawing applications for Japanese assume a basic knowledge of stroke order and number and type of stroke. In the first example above I drew the character with the proper number and type of strokes. You can see at the very top the very first character the application guessed is the correct kanji. The second character may look drawn almost exactly the same, but it isn’t.

Look in the middle of the illustration – it says Strokes: 6. This character is only drawn with 5 strokes. In small stroke character like this it isn’t too problematic, but in significantly more complex characters adding or missing a stroke can make this particular input method daunting. You can see there is a check box to allow the program to guess +- 2 Strokes. Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t.

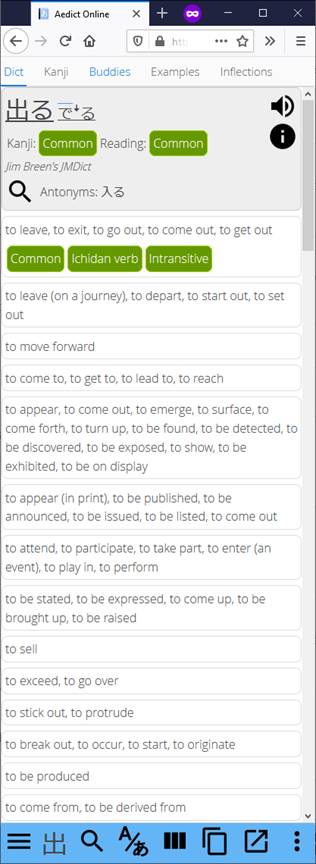

Below Aedict displays both the proper way to draw this character and the definition. I picked “deru” because I find this word maddening. It usage matches up to multiple different English meanings. The definition scrolls on beyond what I have displayed here.

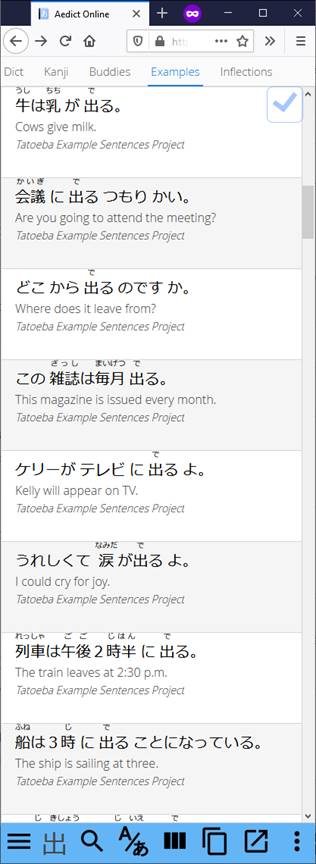

The application also provides other words and other readings that use the same character. It also uses another wonderful public domain project called the Tatoeaba Project that a collection of Japanese sentences and translations in multiple languages.

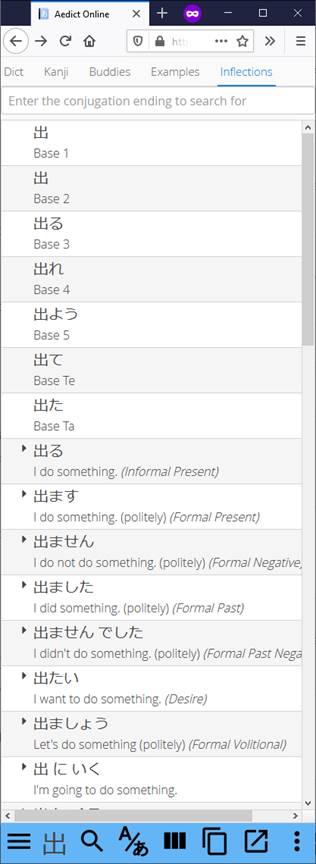

And finally because I chose a verb to look up the dictionary program tells us how to inflect it to make various grammar forms like present and past tenses. In the old days you used to have also input verbs into electronic dictionaries in what is actually called “dictionary form”, but now most dictionary programs, including this one, will “de-inflect” verbs so that you can simply input the word as you read it. That was huge deal because certain Japanese verbs are inflected in one of five ways and it can be difficult to tell which of the five was to use to get the dictionary form.

There you go! Simple right? Happy Japanese learning everyone.

I’m turning Japanese,

I’m turning Japanese,

I really think so…

*goes blind*

You know we (mostly) all want to see it again.

Greatest comment and follow-up comment:

I knew that was the video!

Totally off topic, but I need to vent.

Woman and I were shooting darts. Gets a text from an ex who is home from Vietnam.

Now stuck being host.

Damn it. Just want to chill.

You didn’t throw darts at the ex?

I got this email from my daughter in TX about an hour ago.

“I’m sitting in the Soc Sec parking lot & I can’t move. I’m having a nervous breakdown. I’ve never felt more alone in my life & this is not good”

Did I mention she’s 53 years old? This sort of thing has been on going for years. I think I know the problem but it didn’t start today. THis is not the way retirement is suppose to be.

Geez. Sorry.

Sorry to hear that Fourscore. What do you do next?

Ugh.

Sorry big man. My younger sister is on that track, too.

These sorts of things have been going on her whole adult life, one crisis after another. Yesterday she was upbeat, had all her bills paid, credit cards zeroed.

She thought Prince Charming # 1 was the solution. Wrong from the beginning. Now Prince Charming #2 has swept her off her feet, as of 2 months ago, I think he’s tired of the drama. I’m not smart enough to solve her problems, she wants someone to be responsible for her but that train has left the station.

Worst case she’ll drift back here and want to live in the cabin but she wouldn’t take care of that either. Wait and see. Her kids have moved on with their own lives, fortunately.

Her brother is 60 miles away in Austin but he doesn’t need the problems either.

Sorry buddy. I feel your pain.

Thanks Guys. This isn’t the first crisis nor will it be the last

I’m 51. I feel like your daughter pretty much most of the time.

Except you handle the problems well, responsibly and with dignity. My daughter had many opportunities and wouldn’t accept the responsibility. Her college career was one week (Orientation). 8 o’clock classes are rough.

Another email from my daughter. Crisis apparently has passed. Sounded OK. “Wait ’til tomorrow, maybe she’ll ride on again”

I look at the Japanese characters, shake my head and realize Japanese kids can read/write the language. Japanese kids are way smarter than me.

I find reading and writing Chinese even more daunting. Japanese has the difficulty of multiple readings for the same, but fewer, characters.

Japanese doesn’t have tone like Chinese, does it?

It has pitch accent, but not tones that impact meaning like tonal languages like Chinese.

I can never tell if people speaking Chinese are angry or if it’s just tonal.

All right folks, I’ve got to disappear for an hour or so. If anyone has any questions I’ll answer them when I return.

I’ll leave you now to the wonderful commentary that makes Glibertarians the place we all love.

Shut up, Tulpa!

I’ve used CEDICT a lot for Chinese, modeled after this one. But yeah, the exercise seems even more difficult for Japanese than for Chinese, which doesn’t have the grammatical inflections or multiple readings that Japanese has.

The multiple readings aren’t that hard to get used to except for names. Basically, you’ll see someone’s name written and take a guess. “You’re Jack Daniels?” “No, it’s read as Jim Beam.”

But pronounced “throat warbler mangrove”

Anne Elk appreciates this.

Bah. Kids these days *wipes back of neck with hot towel oyaji style*. I learned using an actual kanji dictionary not some digital cheat. Then again, I’m a radical.

I bought one and quickly said “no way”.

To be honest, I haven’t used it in almost 20 years. Find the radical and count the strokes. Really not that difficult. Same problem you have in English when you were a kid and didn’t have any idea how to spell a word. The teacher would say, “Look it up.” Uhhh.

Where do you start with mess like 薔薇? Especially the second kanji.

I’d have guessed び because of the び in 微妙.

Also, it’d び the same by any name.

Funny enough my browser plug in lists “shoubi” and “soubi” as possible readings.

It’s almost like you speak Japanese…

Or have read Shakespeare. 😉

But is it still as sweet?

I hate puns. For some reason, this is the pun I hate the most, and, by extension, now – you.

I hate puns.

Wait – aren’t you a father?!?

There’s a reason I’m the cool dad.

Then you hate all Japanese by extension. This is the land of the rising pun.

Yes.

That’s like posting the Bengal’s fight song.

ALOL!

Huh…I just ordered dao off of Amazon (budgetary reasons). Was looking at a dadao, but, decided on differently.

Well, without the “on”.

You are just doing this to get a rise out of him.

I’ll admit; at first I thought there was nothing for me in this post. However, while skimming I came across this section…

…and had an epiphany. I collect currency, and my main area of collection is the currency of WWII. I always have trouble with the plethora of Japanese money and Japanese occupation money. I’ve tried memorizing and printing cheat-sheets of common words and phrases. And they help…but this could be a HUGE help. Thanks so much for sharing!

*bows deeply to Sensei-san*

どういたしまして。

Mik ezek a holdrúnák?

Those are the easy ones – not pictograms. ‘You’re welcome.”

(Thank you Google Translate. Which initially translated that to Japanese as that’s how I had it set. これらの月のルーン文字は何ですか)

Oh, I know, I’m enough of a weeb to recognize hiragana when I see it, I just enjoy poking fun. Would have been better if Mike still had his original mooninite avatar.

Tangentially related, Hungarians used a runic script before they adopted the Latin alphabet.

It’s specially hard when you don’t speak any Japanese. One of my Korean friends and I were talking about Korean a few years back and he asked me it I’d like to learn it. Then he showed me some written text. And I said fuck it. Where do you start when you don’t have any common point of reference? I mean English speakers learning Latin languages, OK, at least you have the common alphabet set, but WTF is that Hieroglyphic shit?

Not to sound glib, but from the beginning.

Also Korean is super easy to learn in that every symbol has one and only one sound and articulation.

“Looks at the name of the site” I thought being glib was the point.

Something something GLIBTARD!

“Also Korean is super easy to learn”

Sure, maybe when you have plenty of time for it. That’s the crucial element. Right now, I don’t.

He should’ve said that learning how to read Korean is super easy. The grammar is very similar to Japanese and a therefore a total bitch.

Fine. Edit privilege bullllshite.

Not my fault you all like synthetic agglutinative languages that are head-final.

You don’t like puns, yet you set me up like that?

I’m teaching you self-control.

It’s gradual exposure therapy and not place thicc lines in front of a one day sober addict.

Sír magyarul.

Non-Earthling languages don’t count.

Bah. You sound like one of those damned Romanians.

That’s my understanding too!

Ha, banana was one of the first words I learned to read in Hebrew.

It’s always fruits.

The first word I deciphered in Thai was “lemon”.

“How much” was the first thing I learned in Vietnamese

*winks*

( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

Did you make a lot of money?

Five dolla!

Nah, I was more of a renter

Five dolla love you long time!

rove you rong time. Fi dolla short time

These boots are made for walkin’…

The thing about English is everyone already speaks it. You just have to say it slower and louder if they don’t understand.

There’s plenty of native born Americans who still don’t speak it, at least not very well.

That got a chuckle.

Thread winner.

IIRC Korean is mostly “spelled” and therefore easier to learn to read than Chinese or Japanese.

It’s one of the most perfect writing systems. Each grapheme maps to a distinct phonological feature.

I think if I pick up another language besides half-assed English and whole-assed German, it’s going to be Russian. I’ve been reading about how Russian literature boasts the most beautifully composed form of the novel… and that Russian chicks are super easy.

This was supposed to be its own comment but I am even worse at posting than I am at German.

You could definitely do worse than Russian.

You could be the next this guy.

I’m a simple collective farmer

Did he throw Bernie out?

Wait… am I the adventurous Englishman (?) who tracked down this wily Chernoblyn, or am I the shaky half-invalid he found?

Good lord, he shakes like grandad did with Parkinson’s.

Please please please let it be radiation. Grandad did yield tests for the labs at Los Alamos. Please let the palsy be radiation.

This guy is definitely suffering Parkinson’s. Jesus, he’s a dead ringer for grandad. (Who, during glasnost or whatever, did some observational field tests in Russia in the 80s.)

I shake a lot, but it’s because I drink a whole lot. Maybe that’s his problem, too. But it looks like Parkinson’s. Which isn’t what I have, I just drink a lot.

Every linguist seems to love Korean writing.

It was designed by Top Men.

Apparently It’s Ok to be white is trending on Twitter…. I’m not really wanting to dig into why.

With Japanese, you have hiragana and katakana to ease into kanji. With Mandarin, you have pinyin to sort of ease into the words and sounds, but just have to start plodding with hanzi.

I have a Chinese dictionary for beginners, a paper one. They start with the radical index and then proceed with the character index that has the characters in pinyin (romanization). Then you can look up a word in pinyin in the main body of the dictionary where they are sorted according to the Latin alphabet

I have a son-in-law who is fluent in 5-6 different languages, including Mandarin. I think he’s just pretty gifted at it, but he’s also wealthy enough that he sends me pictures on my cell phone from different points around the globe, at least 6 months of the year. So, there’s that, if you have time and don’t really have to work for a living any longer, taking up most of your time… The other thing is age. My little granddaughter just turned 3 and her mastery of English, German, and Portuguese without ever getting it mixed up is sort of astonishing. I guess when you’re that young and your head is not full yet of mostly useless nonsense, that’s a huge advantage. Barely speaking a 2nd language close to fluency seems a huge effort to me.

It is more effort when you are older. The jury is still out whether or not that’s due to there being some neurolinguistic critical period for language acquisition or if it is just a symptom of the fact that all general learning processes are less efficient as we age.

I still tend to think of it as we have limited storage capacity and well into our modern day careers our storage space is near capacity. I’d love to see that expanded, I’m still curious and full of ambition for learning, but unfortunately, it seems to be limited.

The storage space is full of all those memories from when we were kids.

We maybe tend to preserve the memories we are most fond of. I still can pretty clearly recall certain memories from when I was 4 years old. Nothing I can recall before then.

A couple weeks ago I had a dream and in my dream was this kid, sort of a friend. He took me to his house, near the junior high, when we were about 14, 8-9th grade. Anyway, I thought I remembered his first name (Ronnie) but I couldn’t remember his last name, I puzzled over that for days. Finally it hit me, his last name was Moore.

Ronnie and I weren’t close friends, I hadn’t thought of him for close to 70 years.

There were certain things I remembered about the house, I think we had a sandwich for lunch. That’s why the storage space is filled with extraneous

junk that should be deleted.

I’ve had this conversation recently with co-workers, most of whom are close to the same age as me, senior software engineers, analysts, and directors. My long term memory is extremely sharp. If a client brings up an issue that we’ve touched on before, I can remember it instantly, doesn’t matter if it was a year ago, I’ll be able to rattle off every single detail about it. But I can walk into a different room today and stop and say ‘Wait, why did I come in here? What was I doing?’. And just walk right out and can’t figure why I did that to save my life.

Yup. Happens all the time.

My theory is that the mind disk gets near full and when new data needs storing the new overwrites some old data. Trouble is you don’t get to decide what gets overwirtten.

So, I can still remember when that really cute brunette stood me up in high school. But I can’t remember – will I’ve forgotten.

Thanks for the article, Sensei. Putting these together can be a lot of work.

I bet you’re impressed. You can barely put together a handful of links.

???

I will be the first to admit that Saturday Evening Links are a total phone in.

I’m kidding, man. They’re good.

Don’t you try and butter me up.

::scribbles notes furiously::

Go on…

I’ve been meaning to rant about this for a while. It was cathartic.

So Woke!

No wonder everyone hates America for being such non-woke sexist, xenophobe, homophobic monsters, it’s so much better everywhere else.

Says the guy from Tuplastan.

Is that next to Tulpastan?

Dammit!

All of you Tulpae shall pay when I’m Supreme Overlord of Tulpistan. *at least someone can spell it right and obviously deserves to be Supreme Overlord*

I thought that guy who lives in the garbage can was the Supreme Overlord.

And that pretty much sums up Glibertarians.com.

Saudi Arabia has arrested more than 200 people for violating “public decency” – including by wearing immodest clothing – and “harassment“

Love to hear how they define “harassment”.

I don’t think “the austere kingdom” needs to worry about issuing a tourist visa to me.

I’ll break the grammar down for you easy like. As an American, just imagine speaking Japanese like you are a total asshole. Instead of saying, “I don’t like natto” you should say, “I like natto, NOT!” Instead of saying, “I went to the soapland” say, “Went to the soapland” and point to your chest with your thumb.

Speaking of Asians, does anyone have the score to the Cal game?

That joke makes me want to hear it again an hour later. For ten years straight.

Has it been 10 years? We should have an anniversary celebration.

Time flew by, didn’t it?

OT, but, here we are.

My wife is now at the stage of pregnancy where she’s successfully pissed off everyone around her. I just told her, and I quote, “I know what you’re doing, you’re little ‘bit’, and I’m already ahead of you, and I’m over it.” This went over as you’d expect. My four year old daughter is currently telling her something to that effect, but in a slightly different format. The induction is on the 10th. Not sure if the marriage will last that long.

So, a thing that nobody ever talks about is that while pregnant women are waddling around complaining about how much it sucks to be pregnant, there’s a guy orbiting her picking up all the slack on top of the usual shit he does for her who is getting absolutely no recognition or assistance. But, you know, the patriarchy.

Sorry, should be “your little ‘bit'”. Fury is screwing with my grammar.

Ahem – YKWIM.

I understand the challenge, Bill, but you will have another kid in a few days. That kid may refer to you some day as his/her hero simply because it’s obvious what you do for the family.

Good luck, brother and stay tough. Can’t wait to hear the news!

If I could just find some way to get her to accidentally get high from now until then, I’d be golden. One of my aunts-in-law was telling us this story about how she was having a fight with her husband, my wife’s uncle. She said, “You know what? Maybe you could hold off and only say something critical every third time something occurs to you.” He said, “I already do.” I’d like to keep a chalkboard somewhere to record all the times I didn’t turn into an ax-wielding lunatic. My revenge is that he’s going to be in the 10 pound neighborhood when he comes out. And then, thank God, I can hand this b a Miller Lite and tell her to take it down to a 6.

And then those duaghters turn 16 and realize you are not as powerful as you seem. They learn to work whatever advantage they can get. Stay strong. Bill. you are in for a wild ride.

Can’t you just have a Premie?

He’s past that. We’re in week 37, and he’s 8 and some change. Theoretically, she’s due in mid January, but the scheduled induction is the 10th because he’s huge; if he went to term he’d be over 10 pounds, and nobody’s interested in that shit. Our daughter was big, too; 8 pounds 13 ounces at week 40.

Heh. My youngest kid is 28. That BS was a long time ago.

Her sister was like, “You should have a third one!” We both spit-took. Eff this crap. If we have a third kid we’re gonna have to find it somewhere or something.

hear him!

Just something to think about: The women screaming about patriarchy a) can’t get laid because they are unattractive or fat or entitled or likely all three, b) can’t have kids and/or hate kids, c) too selfish to be in a relationship, d) unable to take care of themselves in the big bad world, and e) secretly want a man to take care of them financially.

Trigglypuff is the very personification of the women I am talking about.

So, that said, on to your situation. I have no advice or anything. You’re a good man. So is my husband.

I don’t miss the things my husband does. Sometimes I forget to say thank you, but I notice and I remember those things. Maybe not specifics, but in my soul, there is a scale of feelings, and on that scale, the things I feel he has done for me far outweigh the things I feel I have done for him.

So, when he needs help, I try to do as much for him as he has done for me, but I can’t. That scale in my soul is ever tilted in my favor.

I don’t know your wife. But if she’s anything like me, she knows. She will remember, not specifics, but that you did more for her than she can ever do for you.

I wouldn’t say someone calling his wife a bitch and having a self-righteous whinefest online is a good man.

You can characterize what I said as a self-righteous whinefest if that’s what you want to do, but I never called my wife a bitch and never would.

“And then, thank God, I can hand this b a Miller Lite and tell her to take it down to a 6.”

What’s the “b”?

Biarritz.

Quite fancy.

It’s a figure of speech. Her running joke is that she can’t wait to be sitting in front of the fire with a Miller Lite and two weeks’ worth of Jeopardy! to catch up on, which is where the Miller Lite bit comes from. I use phrases like, “this b” and “this mf’er” because I say, in actual speech, “b” and “mf’er” rather than actually swear. For good or ill I’ve grown up with patterns of speech that lean on casual profanity, but rather than change those modes of speech I just drop the profane bits. I also say “ess” rather than “shit” typically. If I wanted to call someone a bitch, I’d just call them a bitch.

Lame.

I like mine better.

Honestly, I thought you were referring to something you’d find in a high-end bathroom. It’s a wonder I can be taken in public.

Biarritz.

Also Biarritz.

I don’t remember if you’ve had kids, RAH, so p,ease don’t be offended. The final days of a pregnancy are tough on everybody. I was a little WTF too, but I remember all that kid-having stuff.

It was miserable for everybody involved. Tempers were thin. Patience was nonexistent. Everybody was exhausted. And then the kid came and it got worse for a while.

It’s the lack of sleep.

But what keeps my bitching in check is the remonder that this (husband, kids) is what I wanted. And maybe some days I want something different, but this is still what I want, and I got what I wanted.

Yes, and yes it gets worse for a time.

We’re both older this time around, too, and neither of us have less on our plates than we had when our daughter was on the way. It’s like two cats in a bag and has been for a while. (That’s also a figure of speech; we don’t actually have cats in bags.) It’ll be easier once he’s born because my wife won’t be an understandably stressed-out, uncomfortable, nervous wreck, and we’ll be able to tag-team the baby handling like we did with our daughter. Right now, there’s nothing I can do to make her less pregnant, and she’s not maybe her most considerate self given that she’s got an eight pound child kicking her in the lungs, so nobody’s being their best selves.

We got around the worst by inducing at 39 weeks. Of course, that was after 3 weeks of the OB yanking us around about various issues that all stemmed from a frazzled ultrasound tech doing a shoddy job and flagging a perfectly healthy baby as growth restricted.

Bill, serious here, now. Call the OB tomorrow. Arrange for an induction/C-section ASAP. Fuck the 10th.

We’re inducing at like the very edge of 38 to 39. Initially it was going to be a c-section, but Triceratops (that’s his sister’s name for him) turned the right way at the last minute and the placenta moved, so thank God, no surgery. But, because of advanced maternal age (not my words, and also, what is this, Bolivia?) and the fact that he’s a bowling ball, everyone involved is on board with a scheduled eviction. The great part is that the hospital is literally a ten minute drive from the house, so the logistics are easy, and we’ve got family who can take our daughter while we’re in the hospital for the stay.

@Mo: Earliest we can get is the 10th. 6th was going to be if it was a c-section, but the docs who sign off won’t do it earlier than the 10th.

Second birth is faster than the first. Don’t assume that you have 12 hours to get to the hospital.

We’re almost cocky about this one. Like we’re going to the hospital to pick up a pizza. That’s said, we’ve got everything set up at home, a baby seat in the car, and a suitcase packed. But again, we’re talking about a ten minute drive at worst, so that’s lucky.

*remembers 2nd child’s birth*

*gives Playa the side eye*

Your Milage May Vary.

I wouldn’t make a judgment based on such limited information about a man. People be complex.

Meh, I’m common as muck. Then again, I don’t lose much sleep over what dead hippy sci-fi authors think of me. 🙂

Men like to vent, too. Guarantee that my wife whinges about me to her friends. If she were doing it maliciously, I’d be angry. It’s not and I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt that malice was absent.

There’s also a family culture thing. In my family, the idea that you’d ask someone else to do something for you is almost shameful. It never occurred to me to ask someone to get me a glass of ice water, for instance, in my own home. I know damn good and well where all three of those things are and there’s no reason for me to impose on someone to do something I’m perfectly capable of doing myself. In her family, it’s almost the opposite. Everyone in the family does stuff together and for each other even to the exclusion of other things they could be doing on their own I think because it’s like some sort of demonstration of familial love. To me it’s as if there was some tribe in the Amazon that punched each other in the face to say “I love you.”

I forgot to address this:

That’s how it works in my family. “Hey, honey, since you’re up, can you get me a drink?”

Totally normal.

If they’re already up and not a serious inconvenience…

Holy shit, Mo.

That’s some good stuff there.

Also, and I should’ve said this sooner, that was really kind of you to say and I really do appreciate that.

I’m really not saying this stuff for applause, I’m just dealing with like a few months of walking on eggshells and short fuses and not having any outlets. It is what it is, and I wouldn’t trade what I’ve got for anything, but sometimes I could really use a vacation.

Yes, and in the shadow of yesterday’s conversation about what’s appropriate to say about one’s spouse online came with some contradictory feelings for me:

1st hand: Rude, classless, and totally disrespectful.

2nd hand: Glibs is a community of friends and we act like this place is closed, it’s just us, and we’re all sitting around drinking and shooting the breeze. You (we?) have “known” each other for years and it’s just venting and smetimes you need to vent to your pals.

1st foot: Sometimes somebody is really in trouble and that person has one or two close online communities and that is the only place that person can go for help.

2nd foot: The previous discussion was about people WE don’t know. They’re totally fair game.

I try to be careful about what I say about my wife around others . Not only here, but everywhere. I’ll slip up or vent here or there, but perception has a tendency to become reality, and I’d rather not torpedo my marriage because I couldn’t stop griping. I’ve seen other relationships go sour from exactly that.

It’s generally not a good idea, no. I don’t, but this is kind of a man-cave so some things I just have to roll my eyes and go, “Dude-vent.” Or “He’s drunk.” Or “He’s drunk and venting.”

Yeah, it’s more of a personal line for me than a general edict. It was really important during the rough patches when there was a pile of gripes dancing on the tip of the tongue.

My wife is human and she makes me irate from time to time. But under that thin and fleeting anger is two decades of sharing a life together. As you say, we’ve got a relatively closed circle here and so a little benign venting isn’t a problem. If someone were only bitching about his wife all the time, that would be another story.

Straff and Mojeaux – both correct. Thank you.

You sparked a discussion that probably should be had more often. It’s easy to take the wife for granted. No problems.

You weren’t wrong. I just try to remember this is mostly a man-cave with a well-stocked bar.

FWIW, I think about this place on the second hand and both feet, and would react accordingly. I can be judgmental all day long to strangers in the street. That’s not why I’m here.

TIL courtesy of The Fifth Column: some homes in Brooklyn or whatever won’t let you install a dishwasher, because the covenant requires a separation for kosher and non-kosher dish washing fixtures, but they still require a separate sink for non-kosher wash up.

They have dual-compartment dishwashers. I’ve seen many in Kosher homes.

Do they still have to invite some Goy in off the street to turn off the lights?

(Something else Moynihan has mentioned in the past.)

Timer, or more commonly, just leave them on. Same with the oven.

I think every oven I’ve purchased in the last two decades had “sabbath mode”.

Who knew Ozzy came with your stove?

Most appliances eventually develop a sabbath mode, even if it didn’t ship with it initially.

How much can one charge for that?

Or if wealthy enough simply two dishwashers.

One does not simply two dishwashers…

My wife wanted a dishwasher. I gave her three daughters.

/rimshot

I need to get new numbers for my mailbox, mine are kind of faded, like me…..

Appropriate for the picture on the main Glib page

https://www.therisingwasabi.com/authoritarian-command-named-2019-kanji-of-the-year/

/pines for feudalism

I didn’t vote for You!

/not that I wouldn’t…

Some Japanese cooking for you

https://youtu.be/1GxMpJOM44w

Huh. That worked just fine on mute.

Right at your skill level

I just looked at her tits.

I have to watch each one a couple times to figure out what’s being cooked.

Sorry… what does cooking have to do with the video?

I know I got somethin’ cookin’.

It’s like the modern day version of the gorilla basketball video.

Holy shit. Ha! Didn’t ever notice that.

All I can say is you guys are amazing,

How’s Wendy doing?

Even though I’m in love with a wonderful woman… I consider myself very lucky, after 40 years of complete failure in that love thing. I’d still recommend this as sound advice.

I don’t believe in love

What the fuck is wrong with you people?

Love is the law!

Just don’t love in vain.

Look.

Need more evidence?

Love Removal Machine

“a href= “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhat-xUQ6dw”> “Hush now, don’t you cry,” Tundra.

<a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jhat-xUQ6dw"

My heart hurts, I’m losing my Wendy, Ahhhhh….

I am so sorry, Bob. Words are just not enough.

Prayers for you all, Yusef.

I am sorry.

I am so sorry, Yusef.

I’m so, so sorry Yusef.

Condolences, Yusef, carry on Bro, I know you can, you’re a strong one.

Can’t give you a hug on line. I wish I could…

I am really sorry reading this. I wish there was something I could say or do to make it different.

Pardner, when I think I have problems, I remember you. So sorry to hear that. Words can not express the sadness we all feel in our hearts.

That’s too soon to lose your loved one.

My heart breaks for your situation.

Sorry Bob.

Although we’re not getting Bloomberg commercials, I’m pretty tired of Tom Steyer’s virtue signalling.

Steyer billboards all over Vegas, quite odd to me,

Yeah, he’s way worse than Bloomberg. “I’m going to save the world.” Stuff it.

Hey, look, if we truly went back to free markets, it might hurt muh billionaire status and elevate some you peasants, we can’t have that. Vote for me!

My biggest fear is that if she doesn’t come home this time, she never will, I’m getting used to living alone, but I needs my Wife damnit!

How is her quality of life, Yusef?

Scared and lonely, she’s a long way from home, Bella and Kittah, she can’t relax in a hospital, but she is getting better physically,

Wendy is doing ok, she’s in pain from the drain in he chest, and it’s hard for her to breathe, but no heart surgery needed at this time, just waiting on the stroke scene. this is going to get rough for yours truly….

I’m tired

I’m so sorry, but I’m glad to hear she’s doing OK. I’m praying for the both of you.

But at least you are there for her.

She’s thinking of you, I’d bet. That’s everything.

We are old friends, that’s certain

And hey, if it needs to be said, if there’s anything I can do please don’t hesitate to ask.

-Ann Voskamp

Through the pain and the suffering, she’s still here and you’re still with her. Stay strong, and if there is any weight that can be taken off of your shoulders we’re here to help.

THIS is why I’m still going, can’t stop, against the Rules….

https://twitter.com/HNTurtledove/status/1211797331164590080

Look Its one thing to be so upset at your partisan “enemies”, but wishing that Russia was gone is kinda…. deranged.

https://twitter.com/siano4progress/status/1211820480551903238

LOL

In light of yesterday’s and the above discussions about discussing SO problems, I hearken back to the late-night thread wherein I blabbed my friend’s problem with her dude who had her friend-zoned. He wanted to soend all his time with her and her kids, she wanted more, he wasn’t interested but still wanted all the benefits of insta-family and interesting BFF and couldn’t understand why she cut him off. (At the point your middle-school daughter is excitedly asking you when she’s gonna get a new daddy, it’s time to shit or get off the pot.)

That discussion has not left my mind because the responses were basically, “If he doesn’t want to fuck her now, he never will.”

This was distressing to me because the conflict of Cods & Cuntes is solely that he has friend-zoned her because he has a PTSD-induced aversion to brunettes. He does not want to fuck her, but he wants her company, her advice, her time, her attention, AND wants her to sleep with him (sleep only). She is his bestie, his companion at arms, his second in command.

The “fantasy” here is that he will see the light and stop thinking of her as a male-ish bestie and see her as a desirable woman.

So I will put it to you again in a different context: Is there any way to make you, dudes, believe that he saw the light. My husband is influenced by my extra-story explanations, so I’m not sure he’s reading impartially.

So he’s gay?

He has four mistresses (three of whom are his baby mamas) and three maidservants he fucks tegularly. They are all tall, blonde, and blue-eyed.

Classic gay dude.

Classic golf legend.

No Redheads? I’m offended.

I hate to agree with UCS, but yeah, me too.

I over-use redheads in my books. Had to lie low on that for a while.

I’ve never read any of your books. Any book can be a reader’s first.

Also, there’s no such thing as too many redheads.

😀

True, however, this is an ancestor of my fanbase’s favorite male character, so I’m hearkening to his coloring. Reader has to go, “Oh, THAT’S where he gets the black hair and green eyes.”

Joking aside, the only women I’ve slept next to and not at least considered having sex with were relatives. I have never wanted to snuggle with a dude, and I have male friends I would take a bullet for.

Is the deal that if she were blonde the ptsd would not come into play? Because where the mind is concerned, all bets are off. Remove the block somehow and it’s believable that he could suddenly change his mind, I think.

He has a blonde-haired, blue-eyed fetish that is working in conjunction with this. I removed the block, yes, but I’m not sure the way I did it is buyable. And I don’t even know how to begin trying to explain how I did it in fewer than 50,000 words.

I mean, it could be something as simple as the reality of her replacing the archetype from his childhood, so to speak. Maybe the moment of realization provides such a flood of positive feeling that, well, stuff happens. I guess what I’m saying is that in a world where there are people who can only get it off wearing pony costumes it’s not that far-fetched that a guy could start being into brunettes.

Ah, so he’s a nazi fetishist? They did have impeccable fashion sense.

Sarcasm aside, I don’t suppose something as simple as a wig would work? If it’s a visual trigger that sets off his PTSD, then a wig and a merkin, if such cunte accessories are period appropriate to your setting (though I mostly wanted an excuse to use the word merkin), would do the trick. After the festivities have commenced, have him rip off as he tries to pull her hair. Time the reveal with the height of his climax, and boom, male lizard brain now associates brunettes with orgasm. Might take a few additional ministrations by our heroine to fully alleviate the hesitancy towards raven hair, but seems plausible enough for fantasy psychology.

The “Hey, close your eyes and jerk off in front of me and maybe that’ll work” … didn’t.

Men aren’t cerebral in our lusts, in general; there isn’t a large market for male oriented romance novels while there exists a porn site for every fetish permutation imaginable for a reason. Perhaps the visual aid could fool him better than his imagination. Or maybe not, I write code not novels, I’m a touch out of my depth.

You’re good. I’m getting dude opinions on what’s possible, not what’s most likely.

I have trouble getting past brunette ptsd.

(as in figuring out how such a thing could happen)

When he was a small boy, his older brother told him tales about a beautiful black-haired witch who would come get him if he were naughty, and she would break apart into hundreds of ravens to peck his eyes out. Black hair, black dress. And his brother would taunt him with it endlessly.

But, wait! There’s more!

He and his best friend were pages for knights and they were out in the woods trapping and skinning rabbits. Ravens came from nowhere and beset them, but all they wanted was the meat, but it terrified him.

That’s how.

That makes no sense. But I’m not the romance writer.

That sounds like my ex-girlfriend. Except they were hens she broke into.

I’m not seeing it working.

Maybe the way it’s described in context works better, I donno.

Well, I mean, it’s always better in the context of the whole story. It looks ridiculous on paper, brunette PTSD, but I mean, somebody thought up snakes on a plane, too.

Me personally, if I’m friends with a woman, she already has a chance. As you can guess, I’m not friends with many women. My criteria is personality/face/body. That first one has been the hurdle.

One woman is so time demanding. Imagine having a bunch of them and then one female friend you hang out with all night talking?

Shoot me.

Why would you want that?

He doesn’t TALK to any of the women he fucks.

But he does to friend zone. Cuddles with her all night, right?

I have a question. Is having numerous romantic partners more attractive to a woman? I’ve heard this is so.

Yep. Misses her when she’s mad at him or when he’s gone, loves shooting the breeze with her, takes her advice, laughs with her, jokes around with her, appreciates her presence.

Be more specific. Having numerous romantic partners in the past? Or he’s just a general slut and not gonna change?

Here’s the sweet spot: He’s had a couple to maybe a gazillion women, but he meets you and you are the one and only from now on, forever and ever, amen.

He’s gay then. Putting on heirs. There, a twist ending.

I larfed.

I think there might be some deep seeded problems there. Has he seen a psychiatrist?

I believe it’s set during the hundred years war or something to that effect.

So he died of scurvy, that’s a short story, not a novel.

Scurvy was not a scourge of people living on land at the time.

What food in the British cuisine was supplying the masses with vitimin C?

As an aside, I went and did research into vitamin c sources and the preservation methods that destroy it, and pretty much a whole chock of vegetables provide enough to avoid scurvy unless heated to canning temperatures. If you want to keep vegetable vitamin c intact, pickling is your best bet.

(I did this for Dug’s books, since they are at sea a lot)

Most greens

Cabbage is a good source and relatively common at the time.

That’s just off the top of my head

No, I did not mean to make a pun off of head of cabbage.

But it was funny.

Also, enlightening. Thank you!

Have you considered the possibility that he’s simply not physically attracted to her?

That’s not how romance novels work.

I missed the part where this was about a novel.

OK, so if this is a romance novel, have her give him a handy under the sheets while his eyes are closed. After a few times, they make eye contact during.

Oh, I apologize.

No, my friend’s dude-pal was not attracted to her but still wanted all the benefits of insta-family and her wonderful company.

Anyway, my venting here about that led to the conclusion that “If he hasn’t fucked her by now, he’s not going to.”

And then I got distressed because that’s my novel’s whole conflict.

The nice thing about fiction is you can generally get away with one or two strains of credulity and be forgive my the reader as long as it’s entertaining and engrossing.

PLOTHOLE!

I think we were just talking about real life that the dude wasn’t attracted to her physically. In a romance novel, especially when there is brunette PTSD involved, especially of the witch that turns into ravens and pick your eyes out, it could be plausible.

And further! He is a soldier and is very well aware it’s a problem in his mind. He just hasn’t had a reason to try to get past it before he meets the heroine because he has always simply ignored brunettes altogether.

So he’s TRYING to get past it, but of course the more you try not to think about pink elephants, the more you think about pink elephants.

Heh, heh. This sound like it is internally consistent with the story, which is the important part.

That’s what I’m going for. I just don’t know if my solution is internally consistent.

Can’t explain it in a few words, but I really wanted to know if a dude can friend-zone someone for a long time and then turn around one day and ZOING!

Can he? Yeah, I’d say so. Of course, IRL, there are days/weeks.months/years of minutia that shape things.

Yeah, I don’t think he’s liable to believably change opinion.

Mr. Mojeaux has yet to get that far to tell me if I did it believably or not.

Absolutely possible. Likely? No idea. There were many gals that I didn’t find attractive at first (sometimes even after years) that I finally thought, “On second thought, hell yeah. She’s hawt.”

Thank you! Do you remember what triggered those realizations (especially after years)?

I want to tease him and say it’s the general loosening of standards with age.

Shifting not loosening.

More forgiving lighting. Not kidding. Figurative and literal lighting.

So, vision problems.

Abstinence makes the dick grow harder.

Abstinence makes the church grow fondlers.

Like walking around with

footlongbratwurstpencilcrayon in my pocket.There it is. Knew I was on the right track. Is that yours? Bravo.

*hangs head*

No.

The internet is full of smarter and cleverer and funnier people than I.

There’s a similar subplot involving Gwenda and Wulfric in Follet’s World Without End. No PTSD of course, just a lack of physical attraction on his part at first, then a growing respect and love. Though in that they do have sex, even though he’s still in love (or thinks he is) with the pretty girl he can’t have.

Instead of PTSD, why not have him truly believe something horrible will happen to him or her (or whoever) if he sleeps with her? Then when he finally overcomes his “superstition” it turns out to be actually real. Boom, plot twist! I hear that’s how you get books made into movies.

He spends the entire book low-key scared of her (which is his problem). Then he pisses her off and she plays the raven witch for all it’s worth and his low-key fear blossoms into terror.

But don’t most women want a man who is brave? Seems like he’d have to have something very serious to fear for her (and readers) to maintain respect for him anyway.

Well, he is brave. On the battlefield, he’s fearless. War is the thing he loves most and he sees war as almost human, a woman, a woman he is in love with but can’t have. In fact, he spends the first 2/3 of the book wanting to go back to France and fight by Henry (V)’s side, but Henry needs a political ally, so he’s stuck in England.

1) He is not really AWARE that he’s scared of her, thus, neither is the reader.

2) He actually CAN get it up for her, but that’s when they are arguing and he doesn’t stay for the angry sex. He doesn’t make the connection and she’s not savvy enough to understand.

3) She trips his trigger after she is out with her company of knights, they get ambushed and she engages in battle, killing one man and helping to kill another. Then to him, she becomes War and he can finally have the thing he loves most.

That’s how I solved his selective erectile dysfunction. I don’t know if that’s good enough.

OK, now that all sounds seriously disturbing and very interesting at the same time. Yeah, IMO that’s good enough, messed up for sure, but it definitely works. Lots of character depth and subtext there.

It’s 230,000 words long. There better be some depth and subtext. LOL

http://moriahjovan.com/talesofdunham/thebooks/black-as-knight/

Again, Mo–no offense meant here…every time I see “Black as Knight”, I immediately jump to this gem.

Wowza! That’s a big one.

LOL Diggy I love you.

?tee hee!?

Back atcha, Mo!

Ok Mo, random story because you got me thinking of friendzoning brunettes. Years ago while living abroad I met a Brazilian girl who seemed cool and liked me. We had classes together and finally went out on a date. We enjoyed each other’s company and had some good times. Within a few days we slept together but there was something a bit off. I couldn’t quite put my mind around it. The second time we were together I kept getting this image of a childhood friend in my mind. Then I figured it out. She smelled like Mike Flynn, my best friend in the third grade. It was super weird. It wasn’t a bad smell, it was just my third grade buddy and after I made that connection there was no possible way I could do it again. The thing was I enjoyed her company a lot. I tried to make an excuse that I had a girl coming to visit me and so couldn’t get involved. She didn’t really want to accept that excuse. I tried to set her up with another buddy of mind. Didn’t work. I finally had to break it completely off with her because she didn’t just want to be friends. I really bad about it. But she smelled like my friend.

OMG scents are POWERFUL. I can’t do that to my hero because he’ll never get it up.

Similar story: Son ran out of his own soap, so husband gave him his. It’s strong soap. I took one whiff of my very clean little boy and said, “You don’t get to use daddy’s soap.” He didn’t care, but my husband’s like, WTF?

Dude, I am not going to have my kid smelling like the dude I’m fucking.

On next week’s episode of MTV’s Days of Our Glibs

That kind of story is all the rage on male dominated

romanceporno sites, you could be making bank. Lots of sick folks out there.Yes, you have to switch soaps in that situation. There’s no arguing about it. I hadn’t smelled my childhood buddy in decades or even considered that he had a smell really. She smelled nice until I was close enough to smell the scent of playing football with my friends at ten years old and getting tackled by Mike. It wasn’t even a bad smell, just the opposite of sexual. For a romance novel it might would be better to remember a pleasant scent from the far past that invoked insatiable lust.

I’m probably not helping here, as I can’t recall the specifics. But, I do think I encountered a situation like this at some point. It’s at the periphery of my memory, but, I know it’s very disconcerting.

OMG THAT WILL WORK BINGO!!!! THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU!!!!

As long as it isn’t haggis….

/something exotic, maybe? Silk Road, and all that…

I’ve already got a good idea but it’s gross out of context. Gross in context, too, but it didn’t have to be a GOOD smell.

I wear a peculiar oil, just a drop, on the top of my hair daily.

(Ok, sometimes another touch of the applicator wand to the cleavage)

It’s subtle and lovely, but unique and oft commented upon. “I like your perfume!” From chicks, and “Hmm. Your office smells nice” from dudes.

Hint: it’s fig oil from “The Alchemist” based in Minnesota

The heady mix of blood, viscera, and sword oil?

Alright–I’m voting for

CaputHayeks on this.Hey, she had “cleavage” and “applicator wand”, she wins hands down.

Actually … yes. You’ve been paying attention. Excellent!

Hands down…hands up, or out…whatever works.

I didn’t mean to motorboat her your honor. There was scented oil on her cleavage and the next thing I knew….

Hey–falling face-first into a lovely young lady who is well-endowed, while blowing a very long raspberry, IS an acceptable defense!

And, a rather personal fantasy….

When I was a kid I remember smelling girls hair (not like Joe Biden, just catching subtle whiffs), and it was amazing. Intoxicating. When I met my wife I commented how much I liked her smell and she didn’t wear perfume. Maybe the hero caught the scent of the heroine one passing moment and forgot about it for twenty years.

Oh, no, that didn’t happen. Hero abducts heroine from her wedding. It so happened that she needed to be abducted/rescued. They decide they are each other’s solutions to their problems. But he accidentally abducted the wrong bride.

Allow me to vote up KSue’s point about girls’ hair being intoxicating in many/most situations.

Of course, wrong abduction is what it is. Just wanted to fly my own phreak flag a bit.

I’m already thinking about your next novel Mo. I think you seriously need to consider a Glibs crowd sourced idea. You could get some damn good suggestions here, you might say thicc plot lines. There would be some hilarious, classic, degenerate lines in it. It might get you ostracized or lionized.

Ah, yes–the lion/ostrich hybrid.

“Ostralized”.

The wrong abduction becomes a point of contention. If he’d gotten to the church a little sooner, he’d have gotten a blonde-haired-blue-eyed bride…

…but not nearly as happy about being abducted as the brunette.

@KSuellington, we actually had something rolling the other night that I am seriously turning over in my head. Let me see if I can go find it.

Whoa. You just reminded me of when I started wearing Old Spice deodorant as a teenager, which smelled like the classic cologne. I suddenly started getting interest from an entirely different group of girls.

Tell us the truth, the Old Spice girls were easier, weren’t they?

I do recall some, if not most, of the Spice girls being easy.

I mean, not with me. But, they seemed to get around.

Also, the more I look, the more your avatar is perfect, KS.

I was fond of Easy Spice.

Just throwing this out. Had a friend that I’d meet up for drinks every Friday night for years. He’d gush and gush about how lovely his wife was and chew me out if I said anything that was mildly critical of my wife. “That’s your wife! How can you say that!” Well, I knew his wife and she was seriously one of the kindest, sweetest ladies you could ever meet and very good looking. He waits until she’s in her late 40’s and decides to divorce her and move to Thailand to do what middle age expats do in Thailand.

Point being that I just don’t trust dudes that don’t talk a little, harmless smack about their wives and vice versa. My parents in law always take digs at each other. 45 years happily married. IOW, if it works, who am I to complain?

“move to Thailand to do what middle age expats do in Thailand”

If he’s into little boys, the marriage was doomed from the beginning.

He’s Canadian not German. He ran a literal brothel, lost all his money (yeah, I know), moved back to Canada and became a mailman. He went from being an international banker to that. Served the guy right.

Wait, is this Festus?

Nope. Festus is more along my lines of thinking: Not the most polite person in the world, but not overcompensating for being a true scumbag.

Maybe he got dark hair PTSD?

Only jokingly threw that out because I seem to remember Festus mentioning something about working inside some Canadian Post offices or something like that. The rest of it didn’t fit, and Festus isn’t a jerk. Well, anymore than the rest of us here.

Tone is hard to catch online. It’s why I have Siri read yours in that female Australian accent.

Eerie. I used the Australian accent until the South African one appeared.

Aussie girls

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=SjXVELPIq5k

“Gotta murder a brown snake”

/if you squint your ears

Dusty in here, I’ll be back in a se-se-second!

Fixed it.

You guys always take the low hanging fruit.

You expect more of us? For shame.

What can I say, I’m a Tenacious D fan.

An apt definition of the subject matter.

Kudos, straff

I enjoy spoiling The Crying Game.

And, you should!

You know. I’m standing right here.

We couldn’t see you. The lights were out and you weren’t smiling.

I’m not Wesley Snipes!

True. He has better feelings towards the IRS.

Then be better!

*PRESS RELEASE* Final Hat and the Hair cartoon of the DECADE gets posted tomorrow at 7pm.

So no cartoons in 2020?

/no year zero

Is that like a leap year?

Virtually identical, according to the calendar.

Speaking of British expats, I visited a magical store called Major Market today.

I was just in search of fresh produce, ham hocks, and black eyed peas.

My eye was caught by a big Union Jack up on the wall over a corner of the store. I approached and saw it was a mini Brit Expat section. I came home with Oxford marmalade (the coarse cut kind), black currant preserves, and brandy butter (yes, it’s a thing).

I also noted with pleasure that their selection of English tea was superb, but I’m ok in that department thanks to the Internet.

That was most certainly not my last trip to that place.

I also was struck by the fact that I heard mixed in with the pop music playing over the store speakers the song “Hello my Name is Regret” by Matthew West.

Great song, but not even trying to be subtle about being a Christian song. I was pleased.

Brandy butter is good. I haven’t had it in years.

I’m trying to decide whether to have it on thin crust toast or with scones.

Been a while since I made scones.

Scones.

Thanks to all who advised on the printers earlier.

So whatja get?

Think I’m gonna get a laser for doc printing and an inkjet with photo paper tray option for color and photo needs.

That what we did but the inkjet’s been sitting gathering dust for a long time now.

Despite Tundra’s experience, we’ve had two Brother MFC lasers. The only reason we got another was for a duplexer. Love the double sided printing.

If you didn’t hire a monastery for your printing needs you’re missing out.

The page per minute rate isn’t the greatest, but when it comes to making copies the reproductions are immaculate.

Q: Go for the immaculate conception joke or the “cats walking on your stuff since the 15th century meme?

Not really.

¿Por que no los dos?

“I paid how much for this book,and you left the pawprints in?”

+1 Name of the Rose

Just don’t lick your finger.

Duly noted, hon.

Cue up the Wings…

Man on the run…

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-50952335

Holy cow! How did he get out? Did Japan hire Jeffrey Epstein’s guards?

*whistles*

There are some serious random discussions going on tonight. Spud approves.

Last night I went to bed at the normal person time 9:20pm, so of course that meant I was up bright and early a 3am. So this morning I animated and edited the cartoon, then I cut a tv episode for a client, and now I’m still up 11pm after 15 beers. At 36 I still don’t understand how to sleep.

You are not alone.

Heard that. Went to sleep at 9pm, woke up at 3:30am, farted around online and back to bed at 4:30. Woke up at 9am. New Years vacay is fun.

Anyway, this Bad Lip Reading makes more sense than any of the Disney Star Wars.

I can’t be the only one who watched that and was thinking something other than “stick”.

So this happened.

Let’s hope HM has gone to bed. Looks good.

Ummm, straff…that’s a cheesecake (if memory serves from her story last night).

I don’t think it’s equipped with an actual…. Wait–does HM like cheesecake for desert?

Too bad he doesn’t like puns, because a slice of buccake sounds delicious.

like so?

If that’s for Jameis, someone swoops in and eats it before you can put it your mouth.

No Tampa fans here, eh?

The only football jersey I own is Warren Sapp’s Buc’s jersey. But, that has more to do with the man.

Ewww.

High five for my bro!

It is, indeed, a cheesecake (peppermint), but I am, indeed, not getting the joke.

Well, recall that, up-thread, CPRM says there are a lot of sick fucks out there.

I was merely trying to impugn HM’s considerable character by suggesting he would see the desert in a rather lustful light.

Because, HM. And, I’m just silly.

Also, it was straff what done brought him up in the first place!

True. I’ll own this one. Sorry, MJ. Cake looks ?

He might need the peppermint after eating all that ass.

THANK YOU!!!

Mojeaux, FTW!

BOOM! *mic drop*

Ever hear of how some frats haze rush candidates?

Oh, dear God….

I have no foot to stand on. This is the last cake my kid and I made. Could’ve been from an LGBT frat.

https://imgur.com/a/7BmAiOW

Straf, I mean this in the nicest possible way, but that looks like unicorn puke.

This was 2 pix below yours. Had to share.

https://m.imgur.com/gallery/FRXMtgQ

Tasted like it, too.

Straff has a unique cane decorating technique.

That’s a felching coupler.

Dammit. Out of stock. And it hit almost all the key points I like in a knife.

It cuts things…

That’s one of them.

Sure, you could field dress a deer with a pen knife, but it’d be uncomfortable.

I guess that would depend on your comfort level.

Amazon has it thought.

Yeah, they of everything.

I keed, but the dao I ordered this week.

Dammit…my snark was supposed to be, “Yeah, they think of everything”.

I was too busy thinking about that dao.

I’m trying to tell myself to go back to sleep, since it’s approaching 1am.

I just ordered the cocobolo handle version of the knife.

UCS revealed

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghostface_(identity)

Just read this on FB about Cats. Who was the one seeing it? HM?

Not a jab at you, Mo, but…I can’t even read all of that. And, I probably would agree with the author, if I had any participation in seeing that movie.

It’s okay. I don’t read (or usually post in comments) big walls of text. I thought it was hilarious.

Oh, the part I read was, definitely. For whatever reason(s), I just couldn’t scale the wall.

Sounds like a nightmare made

fleshCGI^This. Using CGI to do Cats is ridiculous. The most interesting part of the musical were the costumes and set.

I heard some of the actors were trashing it.

That was a fun read – thx

?

That wall of texts is giving me TOS flashbacks. Ken Schultz is that you?

Was Ken ever that witty?

Ken didn’t believe in paragraphs.

But, paragraphs believe in him…

/yeah, I don’t get it, either

It sounds so bad that I’m almost tempted to go see it…

Bringing the fragrance discussion down here as a refresh, I’ve read pretty well constructed scientific studies indicating that scent/fragrance is a huge memory trigger, more than all other senses.

Turns out the part of your brain that processes scent is directly next to the hippocampus, which is the brain’s card catalog for retrieving memories.

Part of why people (ahem) with temporal lobe epilepsy often detect a scent before a seizure; that portion of the brain is tickled and affects memory and scent perception at once.

Can confirm.

Just guessing, but I’d assume that evolution dictated we remember smells because …”That smells like the dead buffalo I ate 20 years ago that made me sick as a dog.”

Checks out.

Similar to why we love BBQ. My theory is a Buffalo got struck by lightning in Africa and some early hominids thought “whoah, that smells awesome!”

Plus it was effectively sterilized

Yes, definitely. I have heard a good explanation that deja vu is mostly attributable to smell. I can believe it, certain smells really bring you back.

My pre-seizure auras are definitively deja vu.

I had no idea until my diagnosis at age 33 that it wasn’t normal to get deja vu several times a week, and when sleep deprived several times a day.

I’d just go “Welp. Gonna be a deja vu kinda day I guess.”

As weird as this may sound, when Deja Vu hits, I have taken to doing some kind of anomalous, superfluous physical action–something that I can be certain I didn’t do in the “memory”, so as to disrupt the feeling.

That probably makes no sense, but, it’s what I do.

Isn’t it odd that we have weird things going on that we don’t know are weird because things just never come up in conversation?

“Yeah, I have deja vu a lot.”

“Me too.”

Totes normal. Your “a lot” = several times a day, theirs = a couple of times a week/month, but you assume you’re talking about the same thing and so you never talk about what “a lot” is.

Now my question is: deja vu … did that shit really happen or is your brain fucking with you?

Brain is fucking with you. The hippocampus accidentally misfiles something you’re experiencing now into long term memory instead of short term.

So it echos back as a memory even though you’re a rational being who knows you never have been there or said that.

When it hits while I’m making a presentation or something, I just ignore it and continue on. Nobody knows.

It only lasts 10-30 seconds.

To me, it hits strongly when it sets in. I know what it is, but I’m still thinking “and then he was to my right in a red shirt, and then she stood up over there…”

Highly detailed.

Actually that is quite comforting. Sometimes if I have a deja vu (this doesn’t happen often) I also get very dizzy.

Truth is, If you look at the medical papers and talk to a neurologist, EVERYONE has a seizure threshold.

Some, like me, have a lower one than the general population. That’s why we get diagnosed and medicated for epilepsy.

The “auras” are actually what are called simple partial seizures. You maintain consciousness and control the whole time while having a deja vu or scent or epigastric rising. It is brief.

Then there are complex partials where the guilty seizure center recruits the corresponding lobe on the other half of the brain. At that point you are observably out of it. But it’s brief too.

If the whole brain sympathizes, you get a full up grand mal seizure.

Okay, here starts the thread where we kicked around an idea for a book.

Do No Evil: A Novel

followed up by

OK, Just a Little Bit of Evil: A SequelThings take a naughty, raucous turn…

How the hell did that gt struck? I didn’t put that command in….

Squirrels become gremlins after 0 hour, apparently

In a world where callous and terrible men took what they wanted, there was a woman who would not be taken. She knew from as far back as she could remember, that she owned herself. She wished no harm on any man or woman, but she would defend to the death any attempt to harm the body of anyone she loved.

Methinks Joe Walsh wrote tonight’s theme song.

https://youtu.be/d3XSI_xwvss

Since we’re going eclectic, I’m going with this today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbc7LjMv8Lo

Music from the best private detective show that you’ve never seen.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=M0ymw768TCQ

Best album cover ever. Waiting for Judge Wapner to come walking out with that intro.

I wasn’t trying to be eclectic. I thought the song fit much of the conversation above.

Sorry, I was being acerbic and don’t really know what eclectic means.

Heroes in blue.

The victim is strong in that one. I wonder if there is a union getting involved…

I admit I didn’t see that coming. Good for the owner standing up for his workers.

Damn right!

Hornaday told reporters that the officer told him the incident had been intended as a joke.

Haaaaaaa

“I was takin’ the piss, Chief!”

“And, now, you can take a hike.”

Does anybody remember laughter??

What is this of which you speak?

I didn’t know the origin of the thing except that I’d heard it on O&A. You’re in New York. Surely you remember O&A.

No. I don’t.

With you, I always feel like I’m trying to tell a racist joke in mixed company.

No, I honestly don’t know what “O&A” is

Nor should you. It’s some racist program. Don’t worry about it.

That doesn’t make me wander off.

OK, I’ll bite. Opie & Andy? Never knowingly heard them, just heard of them. Essentially a pair of Howard Sterns? Had to pay extra to get them on the satellite radio, but why bother?

Can media members be banned from using the phrase “into their own hands” in reference to anything…?

She took her personal safety into her own hands, fuckwit. How does that sound, now?

/yeah, yeah–1A

Another 2A victory.

Coincidentally, the new issue of the NRA’s “America’s First Freedom” features as the cover story “The Rise of the Woman Gun Owner”

Ladies and gents, I give the incomparable Mark Steyn.

Goodness, Hayek, it’s barely four in the morning. Too early for your heresies.

I can tell I really don’t want to go to work today. I woke up actually hoping to open the door and see the road covered in glaze ice.

It wasn’t, but I’ll be over it in time to make it to my cube.

I am off today. And I woke up super early to enjoy it courtesy of

inebriationmy dedication to work.I have to drag myself into the office. I also have to pick up something for lunch on the way. It looks like all of yesterday’s ice melted. So I have to get moving.

I’d point out that it’s barely four in the morning, but I’m sure you’d come back with something reasonable like it’s six where you are.

A few more hours to New Years. Spending it at home with the family this years. Mellow Yellow.

Quite rightly.

Do the Japanese celebrate New Years? Or are they recalcitrant like the Chinese, insisting on their own ridiculous calendar?

It’s a big holiday. Countdowns and all. Good luck making it to midnight if you got up at 4.

It was quarter after six when you posted that. I was already on the road, and now I’m in the office, barely eight minutes before my official start of day at 7.

“Gee I hope my workplace burned to the ground so I don’t have earn an honest living.”

Do you people even Free Market ? Turn in your shitlord cards.

Honest living? Was ist das?

Ah yes. You do work for gubmint.

So do I, indirectly, but at least we have to provide value.

Studying the effects of cocaine on the mating habits of quails would never be green lighted by my company, but it was by the fed government

Where did the quails purchase their cocaine?

Oh, probably from Coyotes.

I did that corporate office gig since 1985 and it just got too old to keep doing it.

Now I’m selling my skills contract by contract. I make a hell of a lot more on a daily basis. No freaking way I would go back to that cubicle life again.

I love that spoof song “My Cubicle” to the tune of Youre Beautiful.

I will never return to the cube life again. After 20 cube years, I have the corner office, with a view of palm trees and mountains

I would love to have an office with a door.

Instead they just keep moving my group to worse cubes.

I have a door, but I almost never shut it.

Having your own window ac unit? Priceless.

I remember when I first started with the state, my seat was next to the agency datacenter. I had access to that room, and whenever I wanted to, I could just to in and stand in front of the big AC units there….

Now I don’t have datacenter access, and my cube is in a solar oven that has hit 85 in the winter.

In the Japan version I was the director of my section of the local corporate entity – which gave me the corner desk in the open group area. But that had more to do with the section of the industry I was running (and how that job is done in Japan). I met my Shanghai counterpart a couple weeks ago while working a contract there and he has his own office with a door – but like me it was in the basement.

Did you just see Kiss perform with X JAPAN live on Kouhaku (NHK). Kind of strange.

Yeah, I didn’t recognize Gene Simons at first. But then, I doubt I would have recognized him sitting next to me on a flight from NRT to LAX.

Getting old. Looked like they lip sync’d it.

“Getting” old? I think they arrived some time ago.

I hope you’re still watching NHK (Japanese PBS) and digging this Enka vibe.